By THOMAS W. AURNHAMMER

After moving from New Mexico to Colorado, I must admit that I had a lot to learn about fighting fire in the wildland. I was used to having resources in my former fire department such as water and somewhat adequate staffing. Providing fire protection in rural America was much different than in a municipal setting. I spent considerable time contemplating the similarities and differences between structural and wildland firefighting. One of the most disturbing similarities was that both disciplines seem to have the same issue with multiple line-of-duty deaths (LODDs).

When I took my first National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) S-130: Firefighter Training and S-190: Introduction to Wildland Fire Behavior classes, our instructor told us that two books were must-reads if we wanted to learn about the culture of wildland firefighting. The first is Young Men and Fire, written by Norman Maclean and published after his death with the help of his son, John N. Maclean. The book tells the story of the August 1949 Mann Gulch Fire in Montana in which 13 young smokejumpers made the supreme sacrifice when they were overrun by a blowup (an unexpected increase in fire intensity and spread, enough to prevent fire containment and throw a wrench into whatever plans you had to control the situation) at the fire. The second book is Fire on the Mountain, written by John N. Maclean. It tells the story of the July 1994 South Canyon Fire in Colorado in which a crew of firefighters was also overrun by a blowup in terrain and conditions akin to the Mann Gulch Fire; 14 of those wildland firefighters died in the line of duty.

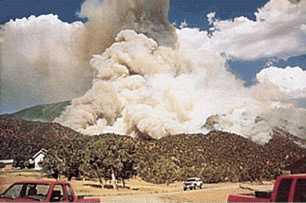

(1) A blowup is an unexpected increase in fire intensity and spread, enough to prevent fire containment and throw a wrench into whatever plans you had to control the situation. (Photo courtesy of BLM Nevada.)

Fast forward to June 2013, when 19 wildland firefighters were killed at the Yarnell Hill Fire in Arizona. In his article “The Yarnell Hill Fire: A Review of Lessons Learned” (International Association of Wildland Fire Newsletter, June 2014), Richard C. McCrea noted, “The real story is Yarnell Hill was much like many other entrapments in the last 20 years and the mistakes made were nothing new. I might as well have been writing about the South Canyon Fire of 1994. Other reviews of entrapment fires during the last 20 years have pointed out many of the same deficiencies in team management and safety practices. Are we condemned to keep making the same mistakes far into the future?”

In providing a comparison of these three tragedies, my hope is to provide critical insight into the dangers of not formulating and maintaining a good situational awareness of a wildland fire incident and to create a better understanding of the culture of wildland firefighting. Structural firefighters working in wildland urban interface (WUI) areas need to have a clear understanding of the complexities of fighting a fire in a structure’s interior and operating in a wildland environment.

The Mann Gulch Fire

The aftermath of the Mann Gulch Fire brought to light the hazards of fire blowups and the need to identify and forecast erratic fire behavior. These blowups often come with powerful convective winds created by the heating of the air that expands and rises while cooler, denser air comes in to replace it. Much like the study of modern fire behavior by structural firefighters, the tragedy at Mann Gulch highlighted the need to study the science of wildland fires. The data gained from fire research continues to impact how these fires are suppressed, without exposing firefighters to unnecessary risks.

How did the fire blowup at Mann Gulch affect the situational awareness of the firefighters that day? In its most basic form, situational awareness is mindfulness of what is occurring around you. We try to use our situational awareness to make sound and safe decisions, but it can be impacted by our location, various interruptions, and the quality of communications. It also includes the hazards to the health and safety of our firefighters. Everyone on the fireground must be aware of what is occurring around them to assist in creating a safer operational environment.

In the beginning, the Mann Gulch Fire must have seemed like a bread-and-butter operation. What about our cultural barriers to creating safer work environments? This relates to both structural and wildland firefighters. Do we allow complacency to gain a foothold in our operations as time passes? Do we truly embrace a safety culture within our organizations?

Both structural and wildland firefighters are at differing stages when it comes to the changing of our culture. Some are completely involved in changing their operations, considering safety for all their endeavors. Others only pay lip service to the issue, with empty talk about solving the problem. Most firefighters see the need for change but require strong leadership to make it happen.

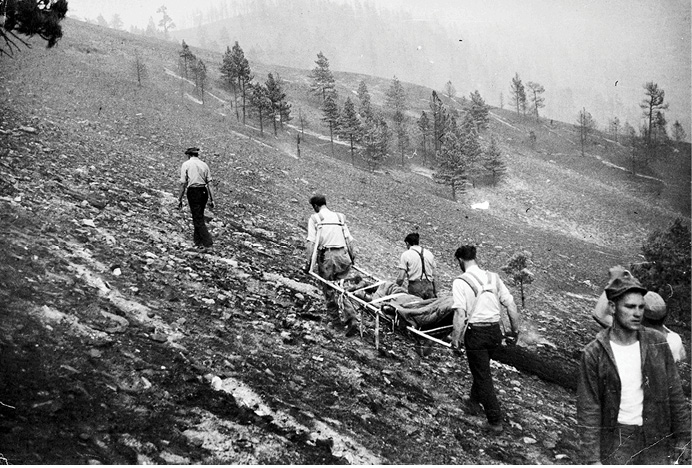

(2) The Mann Gulch Fire in Montana took the lives of 13 smokejumpers when they were overrun by a blowup that occurred at the fire on August 5, 1949. (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service, Dick Wilson, photographer.)

The South Canyon Fire

In the South Canyon Fire, which occurred on Storm King Mountain, 14 firefighters were killed when they were overrun by a sudden and unexpected blowup in one area of the fire. Three major factors were identified that contributed to the blowup:

- The presence of fire in the bottom of a steep narrow canyon.

- Strong up-canyon winds pushed the fire up the canyon.

- The fire moved into previously unburned fuels.

One of the lessons learned was for firefighters to increase their situational awareness. That includes topography, vegetation, and especially the weather. Failure to keep up with information on changing conditions negatively impacts situational awareness and puts firefighters at greater risk. When these relatively small fires grow rapidly and become more complex, information and observations used in the decision-making process may become stress-filled and less reliable.

Several similarities have been noted between the Mann Gulch Fire and the South Canyon Fire. These fires occurred in similar topography, and firefighters at both incidents initially thought they were dealing with relatively routine wildland fires. Weather conditions at Mann Gulch and Storm King Mountain were comparable and, in both incidents, the fire traveled up-canyon and ran over crews with little time for them to react.

After the South Canyon Fire, wildland fire management recognized that, despite increased safety efforts, the same unresolved issues and factors that lie beneath these LODD tragedies were occurring time and time again. In examining methods to reduce the number of fatalities and injuries associated with wildland firefighting, an assessment of the existing culture was undertaken. One of the recommendations from that study was to improve the attitude toward safety, especially in the firefighters who do not seem to have the necessary passion to accomplish the needed changes.

The Yarnell Hill Fire

In 2013, 19 firefighters died at the Yarnell Hill Fire in central Arizona. A crew of firefighters was out on a ridge along the southwest perimeter of the fire. Radio transmissions indicated that the crew was in the “black” (those locations in which the fire has traveled over, with a minimum amount of ground fuels remaining), and the presumption was they would remain in that safe zone. It appears the command staff was not aware that the crew left the “black” and was moving to a new location to the southeast. Shortly after that, outflow winds from a thunderstorm reached the southern perimeter of the fire. With the winds becoming erratic and increasing, the fire turned south and overran the firefighters.

We will never know exactly how the decision to leave the “black” and change locations impacted the crew’s situational awareness. The terrain may have sheltered the crew enough to lose sight of the fire’s behavior. Members may not have felt or seen changes in wind shifts, fire direction, and spread. As the terrain began to flatten, it is likely the crew members knew that the fire was heading directly toward them. Situational awareness is created by amassing information. Part of that information collection involves the interpretation of what is being observed.

(3) On July 6, 1994, 14 wildland firefighters died in the line of duty at the South Canyon Fire in Colorado when they were overrun by a blowup. (Photo from the Fire Engineering Archives.)

(3) On July 6, 1994, 14 wildland firefighters died in the line of duty at the South Canyon Fire in Colorado when they were overrun by a blowup. (Photo from the Fire Engineering Archives.)

(4) On June 30, 2013, 19 firefighters died at the Yarnell Hill Fire in central Arizona when winds at the fire became erratic, causing the fire to turn south and overrun the firefighters. (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.)

The Culture of Wildland Firefighting

The Mann Gulch Fire, the South Canyon Fire, and the Yarnell Hill Fire were all started by lightning in similar terrain. With each of these fires, the fatalities occurred late in the afternoon on days with high temperatures, low humidity, and erratic winds. In all three incidents, the firefighters were overrun by fires that intensified from increased winds. The spread and intensity of fire are impacted by three factors: topography, weather, and fuel. Weather—winds, in particular—plays a major part in the blowup equation.

The culture of firefighting, both structural and wildland, may have been a factor in the decision of the crew to move out of the “black” and relocate to an area where the fire could be engaged. Firefighters are action-oriented people, and that need for action almost becomes part of our identity. Although staying in the “black” would have been a safe decision, it would not appease the need to do what the crew came to do: fight fire.

The thought of creating a new fire service culture, especially one that emphasizes safety, is nothing new. The National Fallen Firefighters Foundation has created the 16 Firefighter Life Safety Initiatives for the Wildland Firefighter. The first initiative relates to culture: “Define and advocate the need for a cultural change within the fire service relating to safety, incorporating leadership, management, supervision, accountability, and personal responsibility. The safety culture within an organization is reflected through its members’ behaviors, attitudes, and actions. Initiative #1 asks us to explore the characteristics of our organizations to bring about a higher commitment to safety and to challenge the belief that the loss of a firefighter is a normal occurrence.” A change is needed to the culture of the firefighter, both structural and wildland, to better understand that safety comes first, and when blowup fires occur, some of the values at risk are going to be lost.

Situational awareness is a concept that has been around the fire service for many years. One of the benefits associated with situational awareness is an increase in safety. We have to look at how it can be integrated into pieces of training and used on actual incidents. Being aware of your surroundings and identifying potentially hazardous situations can sometimes be more of a mindset than a skill. The concept of prefire planning calls for battle planning and for firefighters to think about what we can expect at the various incidents we respond to. Using situational awareness, thinking about what’s happening now and what can happen next, causes you to constantly address the fireground environment for changes that could harm you.

Although safety is always a major concern in structural and wildland firefighting, members of the wildland community took a unique approach to the subject and started examining the human dimensions of wildland firefighting. The emphasis was on the people, not the fire. They examined the role human behavior plays in safety, including common risky behaviors. They also looked at recognition-primed decision making in the context of making decisions in a rapidly changing, high-risk environment. Cultural attitudes were examined from the standpoint of those mindsets being an improvement or impediment to firefighter safety. They recognized how communication, leadership, and group structure can be used to reduce stress and lessen the chance of tragic outcomes. This truly looks like the crossover of situational awareness and firefighter culture. These efforts have led to a list of human factors being included in the Incident Response Pocket Guide, published by the NWCG, as a reminder of what those factors are and how they apply to everyone on the fireground (see sidebar).

Human Factor Barriers to Situation Awareness

Low Experience Level with Local Factors

- Unfamiliar with the area or the organizational structure

Distraction from Primary Task

- Radio traffic

- Conflict

- Previous errors

- Collateral duties

- Incident within an incident

Fatigue

- Carbon monoxide

- Dehydration

- Heat stress

- Poor fitness level can reduce resistance to fatigue

- Being awake 24 hours affects your decision making capability like 0.10 blood alcohol content

Stress Reactions

- Communication deteriorates or grows tense

- Habitual or repetitive behavior

- Target fixation—locking into a course of action; whether it makes sense or not, just try harder

- Action tunneling—focusing on small tasks but ignoring the big picture

- Escalation of commitment—accepting increased risk as completion of task gets near

Hazardous Attitudes

- Invulnerable—that can’t happen to us

- Anti-authority—disregard of the team effort

- Impulsive—do something even if it’s wrong

- Macho—trying to impress or prove something

- Complacent—just another routine fire

- Resigned—we can’t make a difference

- Group think—afraid to speak up or disagree

This article is dedicated to the 46 firefighters who lost their lives in these three incidents. Are we, as firefighters, condemned to repeat the past? If we honor those who have been lost in the line of duty by heeding the lessons learned, we can create a safer work environment.

THOMAS W. AURNHAMMER is a 45-year fire service veteran, is a fifth-generation firefighter, and has served as the fire chief for departments in New Mexico and Colorado. He is a regional captain with the San Juan County (NM) Fire Department. He is a graduate of the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program and has a bachelor of science degree in fire administration. Aurnhammer also has the Chief Fire Officer designation and is a member of the Institution of Fire Engineers, U.S. Branch.