“Every assignment is kind of an adventure.”

(New Mexico In Focus, a Production of NMPBS, YouTube)

SAM MCMANIS Arizona Daily Sun

FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. (AP) — Back home in Flagstaff, retirement resumed, Buck Wickham looks none the worse for wear.

Another fire season will come, soon enough, and he will sure as heck be there once more in the midst of the action. But for now, Buck in winter is content to dust off his golf clubs, scratch his beloved Aussie Shepherd, Bessie, behind the ears, trade his cowboy boots for hiking boots or, really, just chill and reflect on another hot, dry summer on the front lines now safely in the books.

Retirement, understand, is only temp work for Wickham. As he approaches his 68th birthday, he seemingly has every right to take a load off. But that’s not Buck’s style, not even close.

Going on 50 years now, Wickham has crisscrossed the West each summer and fall, fighting fires with the U.S. Forest Service, mostly as part of elite incident management teams that swoop in to remote locales and battle the biggest blazes. Now, bowing only slightly to age, Wickham has settled into the role of section operations chief, overseeing the work and implementing strategy. As part of that job, he also briefs the media and the public with daily fire updates, carried via Facebook during the coronavirus pandemic.

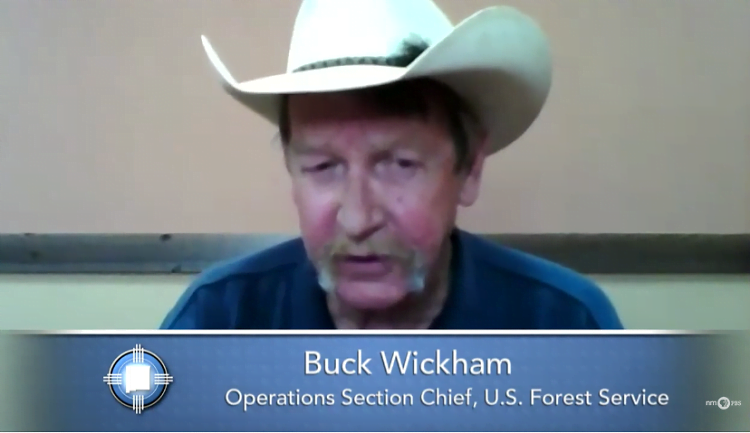

That role, being the public face of fire operations, has given Wickham an unexpected measure of celebrity. At 6-foot-6, with a strapping frame, bushy handlebar mustache and wearing a well-worn cowboy hat, polished belt buckle and scuffed boots, Buck cuts quite a figure pointing to fire maps and explaining such concepts as back burns and fire lines to a worried populace.

Last summer, Wickham presided over no less than seven wildfires in the West, from the Bringham Fire in the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests in early June to the Fork Fire in the northern California Sierra range in early September.

The thing is, Wickham doesn’t need to work so hard. He’s comfortable in semi-retirement with a decent federal pension. But, in another respect, yes, he does need to keep working so hard.

“Quite frankly, I don’t do it for the money,” he said. “I do it for the camaraderie. Every assignment is kind of an adventure. You go places all over the country. I just like being around and supporting the incident management teams.”

He certainly is in his element. You can see Buck on archived Facebook videos speaking softly and carrying a big stick as a pointer on the massive Bighorn Fire north of Tucson, and calming nervous locals with sage updates at the Medio Fire in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where his daily reports became so popular that Facebook heart emojis posted by commenters abounded, and one woman even proposed to him online.

Much of his appeal stems from his demeanor, at once folksy and formidable. Wickham shatters the cliché of the laconic cowboy. He knows how to break down complicated fire management lingo into words that the layperson can understand. And he does so with a well-cultivated sense of humor, both deadpan and sardonic. Sometimes, only the tilt of his mustache is a giveaway.

If they ever made a movie of Buck’s life — he, himself, has already published a memoir about his life and times on the fire lines — no less a personage as Sam Elliott would have to play the lead. Wickham is that dynamic a presence. He sheepishly admits that his real name is Myron, not Buck, but can explain: “When I was born, the doc told my mom I was a buck, not a doe, and ever since then…”

“Buck just has that gift of gab,” said Karen Malis-Clark, a retired forest service public information officer who has known Wickham for 40 years. “He can explain anything and make people understand.”

It’s more than that, though. It’s a certain aura Wickham projects.

“I can’t tell you how many public meetings, pre-COVID, where you’d get 300 or so people in a room with the fire coming toward them, and the anxiety is so high,” said Bill Morse, who works with Wickham on the Southwest Area Incident Management Team. “But Buck gets up and, almost immediately, you can feel the anxiety go way down. He has a command, he shows experience and has a presence. He’s got this old cowboy Western (persona) and people trust him. Plus, he doesn’t B.S. He’ll tell you what’s what.”

He is endearing, no doubt. At the Medio Fire, he garnered something of a fan club among New Mexicans with his straight talk, such as the time he looked straight into the camera and assured people that the fire’s full containment was close, but added, “fire is a dynamic thing and it has made a liar out of me many times before.” At the Bighorn Fire, the gnarled stick from a palo verde tree he used as a pointer became fetishized by Tucsonans. It was such a hit that the incident command team convinced Wickham to record a parody video about the stick, Buck playing it straight with deadpanned seriousness.

Engaging as he is, Wickham is no mere showman. Truth is, he hates all that publicity and accompanying B.S. At heart, he’s still just a wide-eyed boy from Winslow who likes nothing better than to roam the range and commune with the outdoors. None of this celebrity business for him.

“One way to shut Buck down is to build him up,” Morse recalled. “I remember when we went from the fire in New Mexico to the one in California, Buck still had people following him (online) from the Bighorn Fire. One time, we introduced him as the ‘star,’ and Buck didn’t like that. He shut down. He wants to be respected as someone who is an expert, who has paid his dues over the years and earned respect. But still, he’s an icon and sort of the spiritual leader of our incident command team.”

There is, indeed, more to Wickham than his public side. His has been a full, eventful life, both personally and in his chosen profession. He was a single dad and raised his son Joseph in a time when that wasn’t at all common. He turned his childhood aspirations of being a cowboy into long career as a wildfire chaser, interrupted by a brief stint serving in Vietnam.

Over the decades, he’s experienced both successes and setbacks fighting wildfires, mourned in 1976 the loss of three friends who were part of a Mormon Lake Hotshots crew that got caught in a blaze, lamented walking through charred remains of burned-out housing subdivisions, celebrated many a difficult containment effort under extreme weather and terrain conditions — and did all that without losing his sense of wonder, humor and camaraderie with his crews.

And, as he details in his 2018 book, “Spot Fires and Slop-Overs: Memoir of a Firefighter,” Wickham has had enough adventures to, well, fill a book. He was always a kind of prankster among his crewmates, having humorous, not malicious, fun. The book shows a man who both worked and played hard, dousing flames and downing beers in nearly equal measure.

There was the time, early in his career, when he was struck by lightning on the Mogollon Rim. He had been out alone checking out reports of smoke when his tanker got stuck on mud during a monsoon hail storm. Holding a shovel, a bolt of lightning struck a pine tree just feet from Wickham, and he was knocked unconscious and a few feet across the forest floor. He suffered temporary electrical paralysis, but the subsequent fear of lightning was permanent.

Even now, the thought gives him the shivers.

“Oh, hell yeah,” he said. “If it flashes, I’ll flinch. The fear has not gone away. It scared the hell out of me. It rang my bell. I’ve been out in some horrible lightning storms since then, and I’ve entertained a lot of guys laughing at me. Let ’em laugh. It’s hit close to me several times since then. You can hear a real high-pitched whine when it’s gonna hit close to you. About the time you realize what it is, it’s over. I’m paranoid as hell about lightning, me and my dog both.”

He has no fear, however, of fire. Wickham doesn’t like to dramatize his life but, yeah, he’s had some close calls and been caught in some tricky wildfire situations with his teams. In his 20s, Buck was a little wild and took calculated risks, but after becoming a father and raising his son alone — he moved from the Blue Ridge station near the Mogollon Rim to Flagstaff when Joseph started school — he became more circumspect. Smarter about fighting fires, too.

Partly, that came with age and experience. Wickham has been an operations leader for more than 70 fires and seen pretty much all you can see.

His longtime crew cohort, Roy Hall, who traveled the West with Wickham for years, said firefighters looked up to Buck — and not just because of his towering frame.

“On fires,” Hall said, “you find out quickly who has your back and who does not, and when things got bad, Buck Wickham was someone you wanted around.”

The way Hall tells it, Wickham had an almost extraordinary ability to make the right call on the means of fighting fires and what to anticipate. Even in the most trying of circumstances, with the fire burning hot, Wickham kept his cool, Hall said.

One time, in 2001, Wickham and Hall were part of a Type-1 management team called in a stop a raging wildfire threatening Glacier National Park in northern Montana, the Moose Fire. It was rough going. The fire not only had jumped all the lines firefighters had drawn but also jumped the Flathead River, tore through Huckleberry Mountain and was headed for Glacier.

At the end of a long burning period, when the fire was partly subdued by goat rocks because there was nothing left to burn, Wickham drove back solemnly to the command post near Columbia Falls, Hall riding shotgun. Hall broke a long silence.

“We’re the ones who are gonna have to come up with what the plan is,” he told Wickham. “What are we gonna do? Where are we going to start?”

Only then did Buck take his eyes off the road. He stopped the car. The two stared back at the column of smoke rising in the late afternoon haze. Wickham turned and, with deadly calm, said, “Well, you better do some quick thinking. We only got 10 more miles until we get to the command post.”

Hall said the plan Wickham hatched in that last 10 miles of dirt road worked out and “made us look a lot smarter than we were,” Hall remembered. “Buck has that ability to assess a situation and come up with the right call.”

What astounded Hall about Wickham had little to do with the mechanics of firefighting. It was more personal. Hall saw firsthand how Wickham juggled being a wildland firefighter with being a single father. Wickham downplays the difficulty — “I had family and friends who babysat while I was gone,” he said — but Hall could see the toll it took on his friend.

“We had some real private conversations about that,” said Hall, referring to parenting. “It was tough on Buck. It’s a credit to him how everything turned out.”

Buck’s son, Joseph, is grown now and worked as a chef at a Sedona restaurant. What he remembers most about his father during his childhood was not the absences but the times together.

“His time away was small, comparatively,” Joseph said. “We’d spend a lot of time in the forest. We camped together, I guessed, about 2,000 nights. I thought we were camping because it was fun. But it turns out, we were just poor. He taught me about the forest and it didn’t cost any money.

“My dad is a very humble person. He’s saved a lot of people’s lives, but he’d never tell you that. I’ve always thought of my dad as sort of a super hero. A lot of kids think that about their dad growing up. But mine was.”

Joseph laughs at the fact his dad is still out there on the scene of wildfires, pointing his stick right from wrong. That’s so like him, he says, not willing to kick back and chill in retirement. He’s watched the videos and nods knowingly.

“It’s entertaining to me to watch him talk because he doesn’t change the way he’s talking, be it for a YouTube video or anything else,” Joseph said. “It’s great to see him keep it honest and real with himself. It’s great that he still wants to do it.”

But for how long? Malis-Clark marvels at Wickham’s career.

“Where does he get the stamina?” she asked. “I mean, it’s grueling being out there. I have tremendous respect for people like him.”

To which Wickham replies, with a shrug and an ah-shucks gesture, it’s no big thing.

“In my mind,” he said, “I still feel like I’m 26. My body straightens me out pretty often. I guess your body deteriorates faster than your brain, right? I’m going to keep doing it until I can’t.”

All contents © copyright 2020 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.