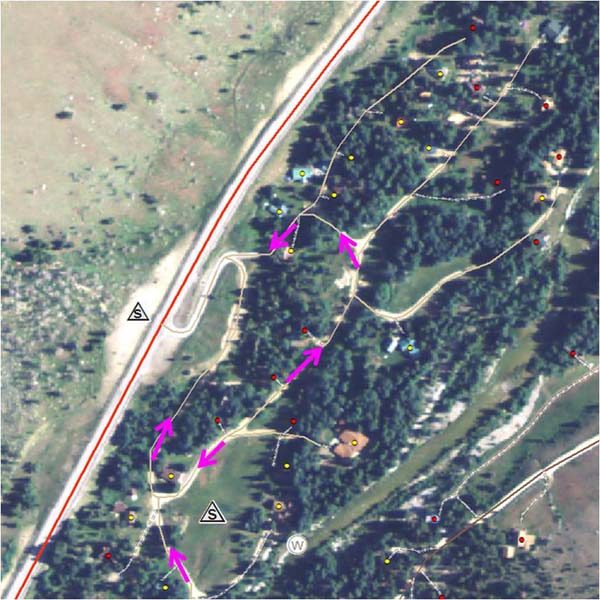

A well-chosen escape route is one that’s scouted ahead of time

One of the keys to safely operating in the WUI: mapping out each neighborhood in your response area, identifying their escape routes and safety zones, and sharing that information with all personnel/departments that will respond to WUI incidents. Photo courtesy Red Lodge Fire Rescue

By Chuck Sallade | FireRescue Magazine Volume 7 Issue 4

In WUI firefighting, our first concern is always life safety, followed by the preservation of property. Our goal is to stop the spread of fire, but in the event that we can’t, we must attempt to prevent the loss of structures (homes, outbuildings and public spaces) that are in the fire’s path. When doing so, we must always maintain a heightened level of situational awareness so that we can recognize potential threats to our self-preservation.

In our fire district, we have several subdivisions with narrow roadways, dense timber, bridges with low maximum weight limits and major geographical limitations (e.g., chimneys, canyons and steep terrain). This may sound like a challenging area; however, through an ongoing effort to develop a current pre-incident action plan and a database of information on the homes within these subdivisions, our department can identify, among other things, safety zones and escape routes (or the lack thereof) for each subdivision and each structure within the subdivisions. This information is then available to us on a call-to-call basis at the touch of a button. (Note: The opportunity to develop the plan and database stems from our experience with the Cross Boundary Grant Program. For more information on this program, read “An Even Exchange,” by Tim Ryan, May 2011 issue, p. 63.)

Our pre-incident action plan allows us to indirectly fight a fire by identifying homes that a) need no protection, b) are defensible with protection or c) have been deemed indefensible. Within each different subdivision, we have homes that fall into each of these categories. As a result, we’ve identified the best safety zones within, or in close proximity to, these subdivisions; we can also identify potential safety zones at some of the structures that we consider defensible. Important: When identifying safety zones, we always base our actions on current and expected fire behavior and weather forecasts.

Safety Zone 101

According to the Fireline Handbook and the Incident Response Pocket Guide (IRPG), 2010 edition, a safety zone can maintain a separation distance of four times between the firefighter and the maximum continuous flame length on all sides (in other words, from the center of the safety zone). For example, sustained 10′ flame lengths require a radius of 40 feet or a safety zone of approximately 80 feet in diameter. So, using these standards, a three-acre safety zone is necessary to accommodate a three-person engine crew facing 50′ flame lengths. This is about the size of three football fields if they were configured into a square.

That said, this safety zone is in a non-dynamic world; it sits on flat ground with no wind. In reality, it would probably need to be much larger to account for certain conditions, such as high winds and steep slopes.

Safety Zone Tips & Tricks

When establishing a safety zone, you must look for or create an area that’s devoid of combustibles and fuels. This means that if you need to create a safety zone, you’ll need to burn out the area prior to the arrival of the flame front if possible. Just remember to avoid setting up a safety zone in chimneys and/or downwind of the flame front, or in saddles or narrow canyons.

You should also avoid setting up a safety zone in or near a house. At the risk of stating the obvious, a house is not a safety zone. Safety zone size calculations are based on radiant heat, which is also what, under certain conditions, can cause a structure to ignite.

On the other hand, if you see that a house has a front yard large enough to conform to the guidelines given above, and it has a lush, short-mowed and green lawn, that’s as good as (if not better than) having to travel to a remote safety zone. Of course, the description of the yard suggests that the house has defensible space around it and is therefore a defensible structure, one that an engine crew could stay with and protect while the flame front passes.

A remote safety zone that will be used by engine crews assigned to structure protection in a subdivision requires another component: an escape route that leads to the designated area.

Escape Routes

I can think of one subdivision within our fire district that has, by definition, no defensible/prep-and-hold structures due to a lack of on-site safety zones in certain conditions and with certain fire behavior. Others have safety zones designated within the subdivision, yet they’re still a short distance from the structures being protected. These circumstances all make it necessary for crews to determine escape routes to the safety zone(s).

A properly chosen escape route, for the purposes of this article, is one that can provide a means of safe ingress and egress for both the crew and its engine. One of the more challenging escape routes that comes to mind is a roadway that forms a loop and has a narrow main access leg. According to Murphy’s Law, this escape route will become clogged by one apparatus entering the area just as all others are trying to escape.

This is exactly what happened to our department a few years ago. During a Type I incident in our district, a task force of apparatus that was privately hired by an insurance group, and that was not in communication with our forces, was heading out of the loop road as we were heading in, thus forcing our engines to reverse out, which took considerable time and effort, and temporarily clogged the escape route. Had we been under more urgent circumstances, this incident could have had a very different outcome.

Likewise, one engine staged facing the wrong direction will hinder the movement of all others within the strike team or task force, and possibly the entire area.

Route Considerations

A well-chosen escape route is one that’s scouted ahead of time for obstacles that could hinder travel, is well-marked for both day and night travel, and is communicated to all who could potentially use it. Other considerations include distance and/or the time it takes to reach the safety zone vs. rate of fire spread, and travel time of the slowest person or engine.

Essentially, an escape route should not be chosen if flame lengths could render it useless by possibly blocking or crossing over it, or if it’s simply too far away from the safety zone. However, where engines are involved, the escape route is usually already chosen; it usually comes in the form of a road. Although the path a road takes typically makes a good escape route, be sure check its entire pathway to confirm that it does in fact adhere to the criteria needed to ensure the safety of all engines and their crews.

Stay Safe

Remember: Safety zones and escape routes are crucial for firefighter safety, particularly on large conflagrations that occur during extreme weather situations, such as high-wind events or extended periods of drought, as we saw in Texas this past year. To ensure safety and property preservation, train regularly on how to determine and maintain safety zones and escape routes, establish them immediately on an incident, and if possible, preplan their locations within at-risk subdivisions in your response area.

Chuck Sallade is the lieutenant in charge of wildland apparatus for the Red Lodge (Mont.) Fire Department